Beginners Guide to Ruby on Rails Performance: Part 1

Update 14 Mar 2025: In the section about empty collections I made a comment that 100,000 objects seemed like a lot when all we want to know is the size. Well, it was a lot. There was a bug in my code which was returning about 100,000 too many objects. I have corrected the code and the object counts. All the other metrics were correct.

This is a written version of a presentation I have given to several Ruby on Rails teams. I cover a list of common mistakes1 that beginner developers (and developers in a hurry) sometimes make that can have negative impacts on your application performance as your app grows. Most of these things aren’t a problem for an app with a small amount of data, but I think it’s a good idea to get into the habit of using these techniques. There’s very little difference in effort between the slow and fast versions of these scenarios so don’t be too concerned about YAGNI or premature optimisation.

It’s also worth reviewing your code occasionally to make sure none of these issues have slipped through.

When I give this presentation I run the benchmarks in the terminal live rather than have folks read them. This means that this post is quite dense. Because of that I have split it into two posts. Part two is here

Beginners Guide to Ruby on Rails Performance: Part 2

Hopefully you can slog your way through and come out with something useful.

TLDR

Don’t call enumerable methods on ActiveRecord collections. Almost all enumerable methods have SQL equivalents and they are functions that a database engine excels at. Use the database Luke.

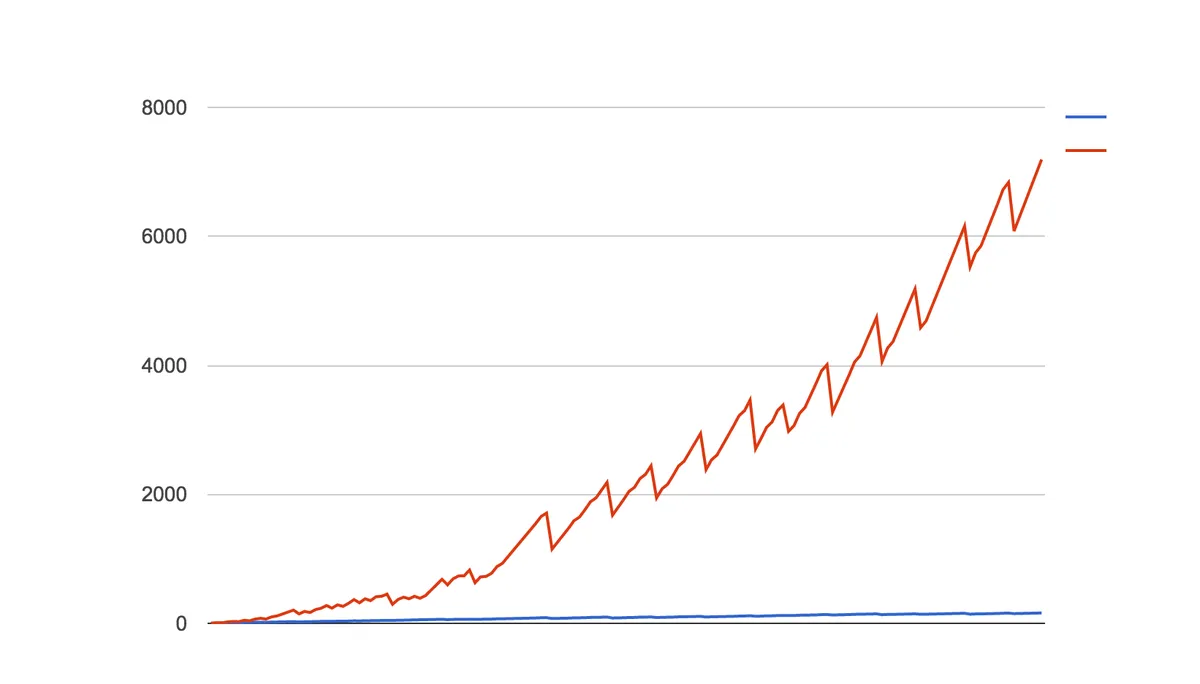

This graph is from a performance optimisation session I carried out on a Ruby on Rails application I worked on. It shows the count of objects created by the application while running the inner loop of the invoice generation process. The red line2 is before and the blue line is after the changes described below were made to the app. These are all very simple changes and as you can see they can make a huge difference.

But, I hear you say, I thought this post is about performance not memory consumption?

Speed vs Memory consumption

In Rails performance and memory consumption are closely linked. If you reduce the memory consumption of your app it will generally go faster, and conversely techniques to make your Rails app go faster will also result in less memory use. This is because building objects is slow and in the case of ActiveRecord objects they require a trip over the network to the database. So the less trips you make to the database and the less records you bring over from the database the better it will be for your application performance and memory consumption.

Counting Things

We have three ways to ask for the size of a collection in Ruby on Rails; length, size and count. They each have different performance characteristics. So which is the best?

TestRecord.count

TestRecord Count (8.5ms) SELECT COUNT(*) FROM "test_records"

Memory Usage: 0.05 MB

GC Runs: 0

Objects Created: 126

TestRecord.all.size

TestRecord Count (0.8ms) SELECT COUNT(*) FROM "test_records"

Memory Usage: 0.02 MB

GC Runs: 0

Objects Created: 121

TestRecord.all.length

TestRecord Load (311.9ms) SELECT "test_records".* FROM "test_records"

Memory Usage: 989.66 MB

GC Runs: 18

Objects Created: 7,001,136

Comparison:

count: 5535.3 i/s

size: 4959.8 i/s - same-ish: difference falls within error

length: 0.4 i/s - 14423.49x slower

length is clearly the loser here. length is an Array method that requires the data to be loaded into an array. There is no point loading your entire dataset into memory just to count it when the database can count the rows for you3. Calling length has created seven objects for each line in the results and triggered 18 garbage collector (GC) sweeps! We can see that both count and size execute a COUNT(*) in the database.

Does it matter which we use out of size and count? Size has a trick up its sleeve. What happens if we have already loaded the collection into memory?

TestRecord.all.size

TestRecord Count (0.6ms) SELECT COUNT(*) FROM "test_records"

TestRecord.all.load

TestRecord Load (468.7ms) SELECT "test_records".* FROM "test_records"

TestRecord.all.size

TestRecord.count

TestRecord Count (0.5ms) SELECT COUNT(*) FROM "test_records"

TestRecord.all.load

TestRecord Load (518.0ms) SELECT "test_records".* FROM "test_records"

TestRecord.count

TestRecord Count (0.5ms) SELECT COUNT(*) FROM "test_records"

What we see here is that size wins because it does the right thing in both cases; it does a COUNT(*) when the collection hasn’t been loaded and it uses Ruby, skipping the trip to the database, when the collection is already in memory. On the other hand count always sends a query.

If we take a look at the source for size we can see that’s exactly what it does.

# lib/active_record/relation.rb

# Returns size of the records.

def size

if loaded?

records.length

else

count(:all)

end

end

Size == 0

There’s a special case for requesting the size of a collection and that’s to determine if the collection is empty.

TestRecord.all.size == 0

We have several ways (too many) to figure out if a collection is empty. blank?, empty?, none?, any? and exists?.

TestRecord.all.blank?

TestRecord Load (345.6ms) SELECT "test_records".* FROM "test_records"

Memory Usage: 299.7 MB

GC Runs: 21

Objects Created: 7,000,023

TestRecord.all.empty?

TestRecord Exists? (0.1ms) SELECT 1 AS one FROM "test_records" LIMIT ? [["LIMIT", 1]]

Memory Usage: 0.00 MB

GC Runs: 0

Objects Created: 122

TestRecord.none?

TestRecord Exists? (0.2ms) SELECT 1 AS one FROM "test_records" LIMIT ? [["LIMIT", 1]]

Memory Usage: 0.00 MB

GC Runs: 0

Objects Created: 122

TestRecord.any?

TestRecord Exists? (0.1ms) SELECT 1 AS one FROM "test_records" LIMIT ? [["LIMIT", 1]]

Memory Usage: 0.0 MB

GC Runs: 0

Objects Created: 123

TestRecord.exists?

TestRecord Exists? (0.1ms) SELECT 1 AS one FROM "test_records" LIMIT ? [["LIMIT", 1]]

Memory Usage: 0.0 MB

GC Runs: 0

Objects Created: 122

blank? loses out here because it’s loaded the entire collection into memory to check for existence (same as length). All the rest are roughly the same. One hundred thousand objects created seems a lot 🤔 4

Comparison:

empty?: 18590.8 i/s

exists?: 18497.7 i/s - same-ish: difference falls within error

any?: 18454.1 i/s - same-ish: difference falls within error

none?: 18346.5 i/s - same-ish: difference falls within error

size == 0: 5089.5 i/s - 3.65x slower

Here we see the problem with count. For one million rows it’s four times slower for the database to count things than checking if the rows exist. It’s still pretty fast though.

Let’s see if any of these do the right thing if the collection is loaded?

TestRecord.all.empty?

TestRecord Exists? (0.0ms) SELECT 1 AS one FROM "test_records" LIMIT ? [["LIMIT", 1]]

TestRecord Load (294.5ms) SELECT "test_records".* FROM "test_records"

TestRecord.none?

TestRecord Exists? (0.1ms) SELECT 1 AS one FROM "test_records" LIMIT ? [["LIMIT", 1]]

TestRecord Load (415.6ms) SELECT "test_records".* FROM "test_records"

TestRecord.any?

TestRecord Exists? (0.1ms) SELECT 1 AS one FROM "test_records" LIMIT ? [["LIMIT", 1]]

TestRecord Load (426.1ms) SELECT "test_records".* FROM "test_records"

TestRecord.exists?

TestRecord Exists? (0.1ms) SELECT 1 AS one FROM "test_records" LIMIT ? [["LIMIT", 1]]

TestRecord Load (235.4ms) SELECT "test_records".* FROM "test_records"

TestRecord Exists? (0.1ms) SELECT 1 AS one FROM "test_records" LIMIT ? [["LIMIT", 1]]

TestRecord.all.blank?

TestRecord Load (249.8ms) SELECT "test_records".* FROM "test_records"

exists? always hits the database whereas the other three do the right thing. Up to you which you chose.

It’s worth noting that blank? doesn’t make the second call either and it could be argued if you are sure you are going to load the records then blank? is the way to go. Checking for an empty collection is often done when you’re rendering a table of records. Unless you’re rendering filter results, how often is your table empty? Even so I think it might be safer to go with one of the others. The cost of an extra SELECT 1 AS one is pretty small.

find & where take a collection

It always surprises me when people don’t know about this. It seems like a "principle of least surprise" POLS to me; just try it and it see what happens.

There’s a pattern that I’ve seen quite often in apps I have worked on where the code builds a list of model ids and then uses the ids to collect a list of models. This might have been a hold over from when ActiveRecord didn’t support OR or it could be the ids are being collected from different model associations and then you want to combine the list in some way. The code usually looks something like the following

colour_ds = red_ids + green_ids + indigo_ids

# Find records that are red OR green OR indigo

colour_ids.collect do |id|

TestRecord.find(id)

end

In my database there are 285191 records that match.

Time: 10.733843 seconds

Memory Usage: 53.56 MB

GC Runs: 42

Objects Created: 3,161,283

That’s a lot memory churn. Iterating over the colour_ids must create a lot of garbage. There’s no need to iterate over the list collecting the records. Both find and where can take an array as their arguments. Passing a list into these methods creates a WHERE IN () query, eg

SELECT "test_records".* FROM "test_records" WHERE "test_records"."id" IN (1, 16, 19, 30, 33, 38, 45, ...)

TestRecord.where(id: colour_ids)

Memory Usage: 55.89 MB

GC Runs: 8

Objects Created: 2,004,608

TestRecord.find(colour_ids)

Memory Usage: 78.2 MB

GC Runs: 13

Objects Created: 2,290,990

Comparison:

where: 0.8 i/s

find: 0.6 i/s - 1.26x slower

The difference between find and where is find returns an Array and where returns an ActiveRecord::Relation. This means that find will evaluate the query immediately but where will only evaluate the query when you try to enumerate the relation or access one of the objects in the relation. So use where if you think you might have more processing to do on your list of ids. For these tests I forced where to execute the query to make it a fair comparison.

While find is restricted to ids where can take lists of other types. For example strings

warm_hues = Colour.where(name: %w|red orange yellow|).pluck(:id) # <--- spoilers

warm_records = TestRecord.where(colour_id: warm_hues)

TestRecord Load (2.0ms) SELECT "test_records".* FROM "test_records" WHERE "test_records"."colour_id" IN (?, ?, ?) /* loading for pp */ LIMIT ? [["colour_id", 1], ["colour_id", 2], ["colour_id", 3]

models

warm_hues = Colour.where(name: %w|red orange yellow|)

warm_records = TestRecord.where(colour: warm_hues)

TestRecord Load (1.3ms) SELECT "test_records".* FROM "test_records" WHERE "test_records"."colour_id" IN (SELECT "colours"."id" FROM "colours" WHERE "colours"."name" IN (?, ?, ?)) /* loading for pp */ LIMIT ? [["name", "red"], ["name", "orange"], ["name", "yellow"]

even embedded queries

warm_records = TestRecord.where(colour: Colour.where(name: %w|red orange yellow|))

TestRecord Load (0.3ms) SELECT "test_records".* FROM "test_records" WHERE "test_records"."colour_id" IN (SELECT "colours"."id" FROM "colours" WHERE "colours"."name" IN (?, ?, ?)) /* loading for pp */ LIMIT ? [["name", "red"], ["name", "orange"], ["name", "yellow"]

You can see from the generated queries that the second two are the same. ActiveRecord converts the list of Colours into a sub query and queries the colour_id column. I half expected ActiveRecord to convert the warm_hues in the second example into a list of ids.

collect / map

In the previous section we talked about using a list of ids to find a collection of records. But really, if you find yourself wanting a list of record ids maybe you should take a break and re-evaluate your algorithm. There are better way to retrieve records, some of which we’ll look at later. But if it turns out you really need them then there are better ways to do this than mapping over a collection.

TestRecord.where(colour_id: red_id).map {|t| t.id }

First we have pluck. pluck takes field names and returns an array of values.

TestRecord.where(colour_id: red_id).pluck(:id)

And second, Rails thinks this is so common that there is a method just for this purpose, the ids method.

TestRecord.where(colour_id: red_id).ids

There’s also select but that’s the similar to map in that it’s going to create the ActiveRecord objects. They won’t be fully built so I’d expect a little less memory but we’re still going to be spending time constructing them.

Comparison:

ids: 15.6 i/s

pluck: 15.1 i/s - same-ish: difference falls within error

select: 3.4 i/s - 4.58x slower

map: 2.8 i/s - 5.50x slower

As we could have guessed the timings for pluck and ids are the same-ish and map and select are roughly the same.

TestRecord.where(colour_id: red_id).map {|t| t.id }

TestRecord Load (103.4ms) SELECT "test_records".* FROM "test_records" WHERE "test_records"."colour_id" = ? [["colour_id", 1]]

Memory Usage: 138.58 MB

GC Runs: 9

Objects Created: 1,001,432

TestRecord.where(colour_id: red_id).select(:id)

TestRecord Load (75.7ms) SELECT "test_records"."id" FROM "test_records" WHERE "test_records"."colour_id" = ? [["colour_id", 1]]

Memory Usage: 30.63 MB

GC Runs: 8

Objects Created: 1,001,024

TestRecord.where(colour_id: red_id).pluck(:id)

TestRecord Pluck (75.8ms) SELECT "test_records"."id" FROM "test_records" WHERE "test_records"."colour_id" = ? [["colour_id", 1]]

Memory Usage: 7.67 MB

GC Runs: 4

Objects Created: 143,114

TestRecord.where(colour_id: red_id).ids

TestRecord Ids (78.3ms) SELECT "test_records"."id" FROM "test_records" WHERE "test_records"."colour_id" = ? [["colour_id", 1]]

Memory Usage: 2.5 MB

GC Runs: 1

Objects Created: 143,080

pluck and ids are basically the same in that they both return an array of ids. select and map both return lists of ActiveRecord objects even though select doesn’t build complete objects. It’s interesting that ids uses much less memory.

There might be a couple of reasons you might favour grabbing a list of ids vs a list of models.

- It’s a lot cheaper to pluck the ids than collecting models as we have just seen.

- Your id list might have been constructed by referencing different tables.

Anytime you can get by with a list of fields rather than the entire model reach for pluck. pluck has been able to take multiple fields since v4 which makes it even more useful.

Colour.pluck(:name, :code)

# => [["red", "#FF0000"], ["orange", "#FFA500"], ["yellow", "#FFFF00"], ["green", "#008000"], ["blue", "#0000FF"], ["indigo", "#4B0082"], ["violet", "#8F00FF"]]

Filtering

The Enumerable module has a group of functions for filtering collections and it’s tempting to reach for them first. But do you know what else is really good at filtering? The database!

Find the First Record

detect / find5 and find_by return the first6 matching record.

TestRecord.detect

[Lots of queries]

Memory Usage: 987.38 MB

GC Runs: 16

Objects Created: 7,000,678

TestRecord.find_by

TestRecord Load (0.1ms) SELECT "test_records".* FROM "test_records" WHERE "test_records"."colour_id" = ? LIMIT ? [["colour_id", 1], ["LIMIT", 1]]

Memory Usage: 0.03 MB

GC Runs: 0

Objects Created: 196

Comparison:

find_by: 26218.3 i/s

detect: 0.3 i/s - 88151.81x slower

Oof! detect operates on enumerables which means we have to load the entire data set into memory first. Note the LIMIT 1 in the find_by query. Also note there is no ORDER so in PostgreSQL especially the first record could be non-deterministic. You should tell the database what first means by telling it what to sort by.

Comparison:

find_by: 26239.7 i/s

find_by ordered: 33.0 i/s - 794.96x slower

detect: 0.4 i/s - 64544.30x slower

ORDER does have an impact on performance. If you progress to optimising SQL queries you’ll learn it’s recommended to avoid sorting until the last possible moment when you have the smallest subset to sort.

Find all the Things

select / find_all and where are equivalent when you want to return ALL matches.

Invoice.all.select { |invoice| invoice.status == 'paid' }

Invoice.all.select { |invoice| invoice.status == 'paid' }

Invoice Load (12.5ms) SELECT "invoices".* FROM "invoices"

Memory Usage: 1.95 MB

GC Runs: 1

Objects Created: 15,192

Invoice.where(status: 'paid')

Invoice.where(status: 'paid').load

Invoice Load (3.3ms) SELECT "invoices".* FROM "invoices" WHERE "invoices"."status" = ? [["status", "paid"]]

Memory Usage: 0.16 MB

GC Runs: 0

Objects Created: 2,672

Comparison:

where: 1795.2 i/s

select: 368.0 i/s - 4.88x slower

Same story repeating here. select loads all the records whereas where just loads the records we ask for.

We can match on multiple parameters.

Invoice.all.select { |invoice| invoice.status == 'paid' && invoice.estimated? }

Invoice.where(status: 'paid', estimated: true)

Invoice Load (0.2ms) SELECT "invoices".* FROM "invoices" WHERE "invoices"."status" = ? AND "invoices"."estimated" = ? [["status", "paid"], ["estimated", 1]]

Multiple parameters to where is an AND. There was a time when ActiveRecord didn’t support OR clauses but it was added in Rails 5. The or syntax is a bit janky IMO but at least we have it now.

Invoice.all.select { |invoice| invoice.status == 'paid' || invoice.status == 'process' }

Invoice.all.select { |invoice| %w[paid process].include?(invoice.status) }

Invoice.where(status: 'paid').or(Invoice.where(status: 'process'))

Invoice Load (0.2ms) SELECT "invoices".* FROM "invoices" WHERE ("invoices"."status" = ? OR "invoices"."status" = ?) [["status", "paid"], ["status", "process"]]

where.not and reject do the inverse.

Invoice.all.reject { |invoice| invoice.status == 'paid' && invoice.estimated? }

Invoice Load (2.0ms) SELECT "invoices".* FROM "invoices"

Memory Usage: 0.03 MB

GC Runs: 0

Objects Created: 11,794

Invoice.where.not(status: 'paid', estimated: true)

Invoice Load (2.1ms) SELECT "invoices".* FROM "invoices" WHERE NOT ("invoices"."status" = ? AND "invoices"."estimated" = ?) [["status", "paid"], ["estimated", 1]]

Memory Usage: 0.02 MB

GC Runs: 0

Objects Created: 10,312

Comparison:

where not: 477.8 i/s

reject: 376.1 i/s - 1.27x slower

There’s not a lot of difference here. It’s might be because of my sample data. Rubocop complains about the where.not with a “WhereNotWithMultipleConditions” warning. This is because the query generated by this was changed in Rail 6.1. If you are on Rails 6.0 or earlier tread carefully.

Sorting

I hope by now it’s obvious what to do about sorting. It’s another thing that databases are quite good at. If you plan to sort your records, request them sorted from the database.

Invoice.all.sort_by(&:status)

Invoice.order(:status)

Invoice.all.sort_by(&:status)

Invoice Load (13.7ms) SELECT "invoices".* FROM "invoices"

Memory Usage: 2.08 MB

GC Runs: 1

Objects Created: 15,173

Invoice.order(:status)

Invoice Load (2.6ms) SELECT "invoices".* FROM "invoices" ORDER BY "invoices"."status" ASC

Memory Usage: 0.05 MB

GC Runs: 0

Objects Created: 10,821

Comparison:

order: 427.2 i/s

sort: 376.3 i/s - 1.14x slower

Sorting is quite fast in Ruby so the difference in bare performance isn’t that great but if you can avoid the extra work that’s a good thing. The fastest code is the code that never executes.

That’s it for Part 1. Take a break and come back for Part 2 here Beginners Guide to Ruby on Rails Performance: Part 2

They’re not really mistakes because Ruby on Rails kind of encourages you to write this style of code.↩

The graph has a saw tooth because a

GC.startwas added to the end of each loop in an effort to slow the memory growth. Also note the growth is exponential!↩You might have heard

countis slow in Postgres This only becomes an issue with large data sets in which case it’s still going to be faster than loading all the rows and counting them in Ruby. If you are concerned about it you can add a counter cache↩This was a bug in my object counter. It’s now fixed.↩

detectandfindare aliases for the same method.selectandfind_allare also aliases.↩find_byalways catches me out. I spend a lot of time wondering why I only got one record back. It’s a poorly named method IMO.↩